Introduction

When we originally introduced the concept of selective replication over two years ago, we had promising ideas and some early data. Today, we have robust experimental results and a much clearer picture of how selective replication can be engineered reliably in RNA viruses.

Back then, we focused on an OFF-switch design. Since then, we have successfully implemented a fully functional ON-switch, giving us precise control over viral replication based on cancer-specific proteins.

In this post we want to update you on how we use aptazyme to control replication to make our viral cancer therapies much more selective.

What is an aptazyme

Selective replication is straightforward for DNA viruses: you can place key genes under cancer-specific promoters and control transcription. For RNA viruses however, this strategy does not work. Once the RNA genome enters the cell, it is already the final product — there is no transcriptional checkpoint to exploit.

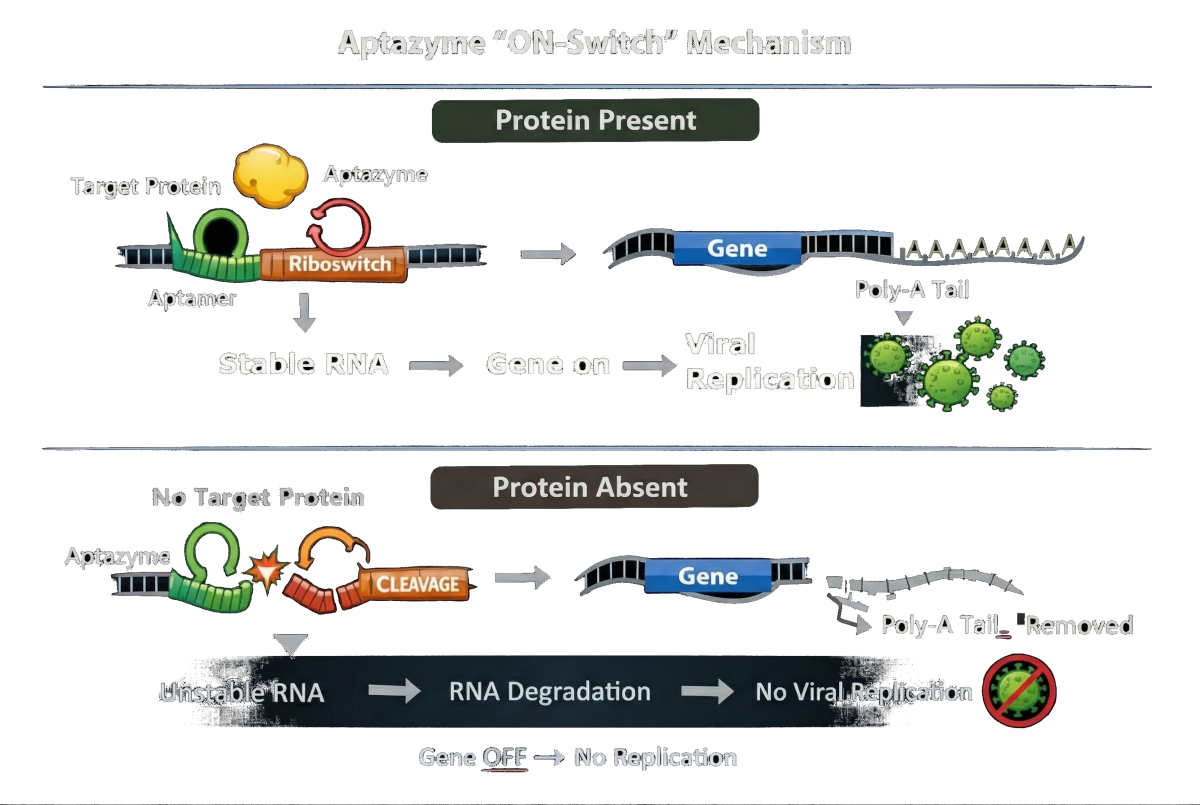

This is where aptazymes come in. An aptazyme is a self-regulating RNA element composed of two parts:

- an aptamer — a short RNA sequence that binds a specific protein

- a riboswitch — a catalytic RNA structure that can cleave itself

Together, they form a sensor + actuator. When the target protein is present, the RNA changes shape and either allows or prevents cleavage, thereby controlling whether the RNA remains stable and functional.

How does an on-switch work and how have we implemented it?

Using an aptazyme, we can regulate gene expression directly at the RNA level by inserting the sensor between the coding sequence of a gene and its poly-A tail. This placement is critical.

If the target protein is present, it binds the aptamer, stabilizing the RNA structure. In this state, the riboswitch does not cleave. The poly-A tail remains attached, the RNA stays stable, and the gene is translated normally. As a result an essential viral protein is expressed and the virus can replicate.

If the target protein is absent, the aptazyme adopts a different structure that activates self-cleavage. Once cleavage occurs, the poly-A tail is removed from the RNA molecule. Without its poly-A tail, the RNA becomes unstable and is rapidly degraded by the cell, effectively shutting off gene expression.

In short:

Protein present → RNA stable → gene ON – replication

Protein absent → RNA cleaved → gene OFF – no viral replication

This allows us to convert the presence of a cancer-specific protein directly into a molecular decision about if viral replication — is allowed to proceed.

What are our results?

Using plasmids to test aptazymes

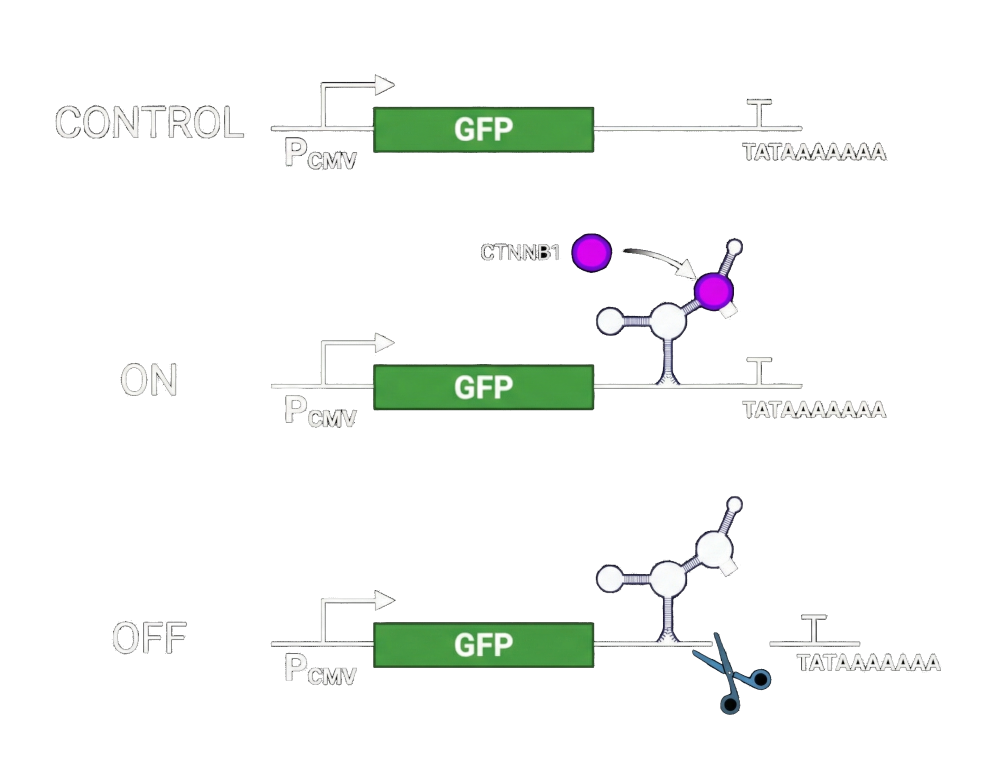

In the absence of an aptazyme, the RNA transcript remains fully stable and GFP is expressed at high levels, serving as our baseline.

ON state (protein present):

When the target protein is present, it binds the aptamer and stabilizes the aptazyme structure. This stabilization prevents ribozyme self-cleavage, allowing the transcript to remain intact. As a result, the gene of interest is fully expressed — GFP in this experiment, and an essential viral gene in the therapeutic context.

OFF state (protein absent):

When the target protein is absent, the aptazyme adopts its active conformation. The ribozyme self-cleaves, removing the poly(A) tail or destabilizing element. Without poly(A) protection, the RNA is rapidly degraded, effectively shutting down gene expression.

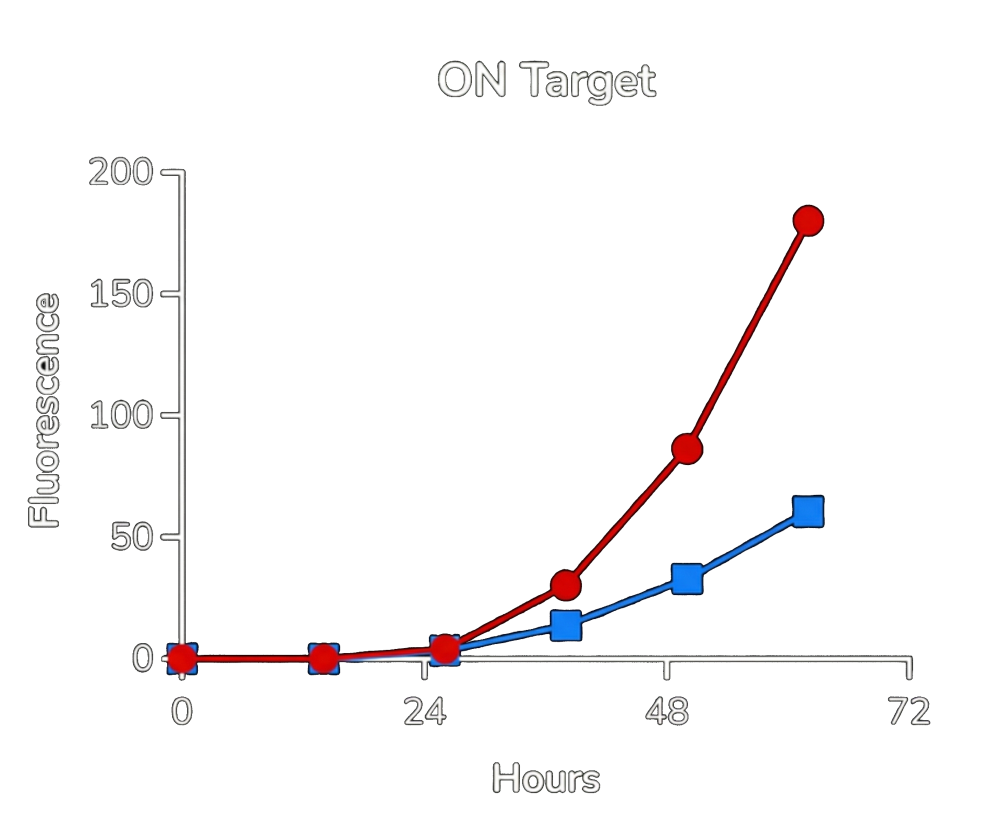

Red: control. Blue: aptazyme controlled expression present.

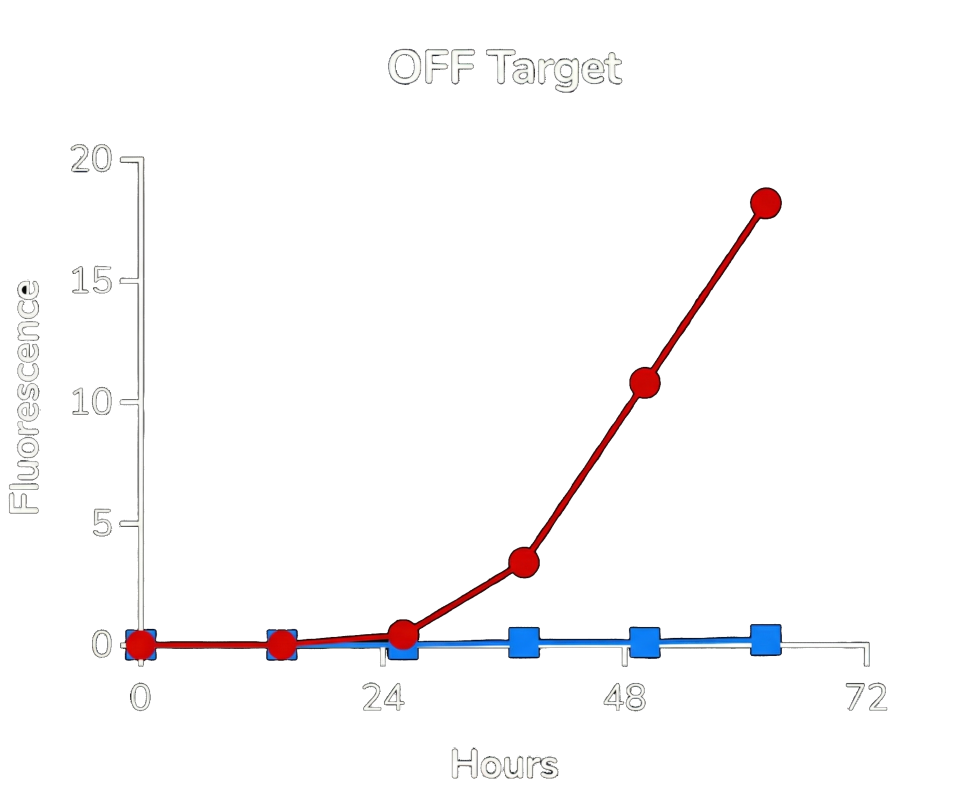

Red: control. Blue: aptazyme controlled expression not present.

From the experimental data (shown in Fig.3. and Fig.4.), two key conclusions emerge:

-

High selectivity:

In the presence of the target protein, GFP expression is robust (blue curve). In its absence, expression is nearly eliminated — approaching background levels. -

Strong safety profile:

While ON-state expression with the aptazyme is slightly lower than the control construct, the OFF-state leakage is extremely low. In practical terms, this means the system strongly favors safety over maximal expression — an important property for therapeutic viral replication.

Using the aptazyme to control viral replication

Plasmid assays alone are not sufficient to demonstrate therapeutic relevance. RNA viruses replicate rapidly, amplify their genomes, and exert potent cytolytic effects. The true test, therefore, is whether aptazymes can function as effective replication switches inside a fully replication-competent virus. In this case especially in the virus we use: VSV.

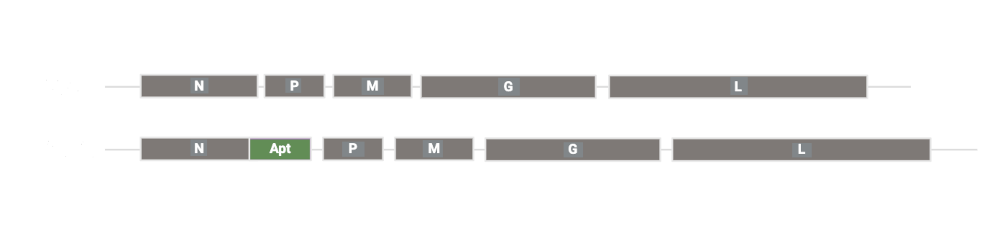

To answer that question, we engineered a prototype virus, HGI536, in which a CTNNB1-responsive aptazyme was placed in the untranslated region of an essential VSV gene (design is shown in Fig. 5 above). This design directly couples viral replication to the intracellular presence of a cancer-associated biomarker.

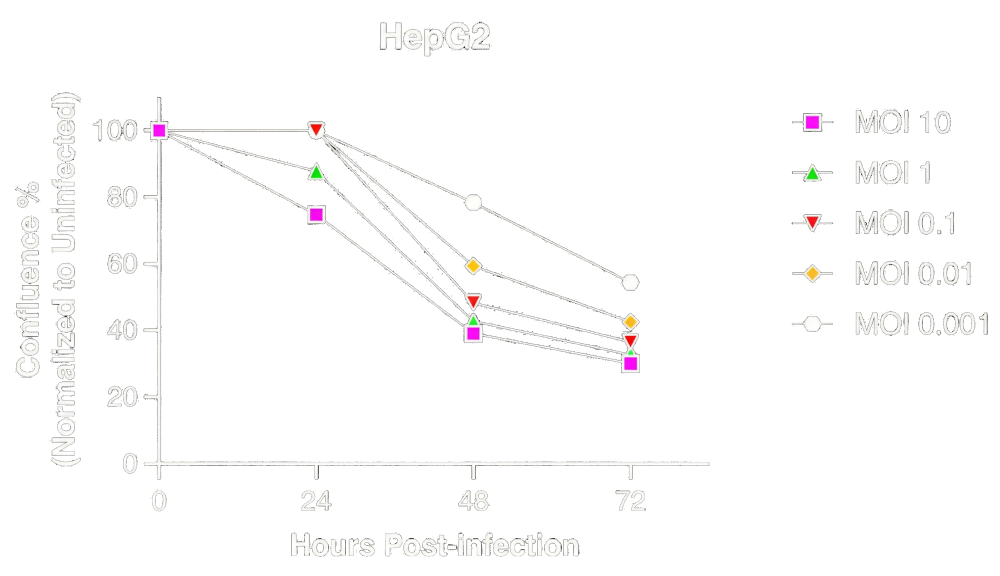

In CTNNB1-positive HepG2 cells, HGI536 produces robust, dose-dependent loss of cell confluence across a wide range of MOIs (as you can see in Fig.6. above). This is consistent with efficient viral replication and oncolysis. The presence of the aptazyme does not measurably attenuate viral activity — demonstrating that selective replication can be achieved without sacrificing cytolytic potency in biomarker-positive cancer cells.

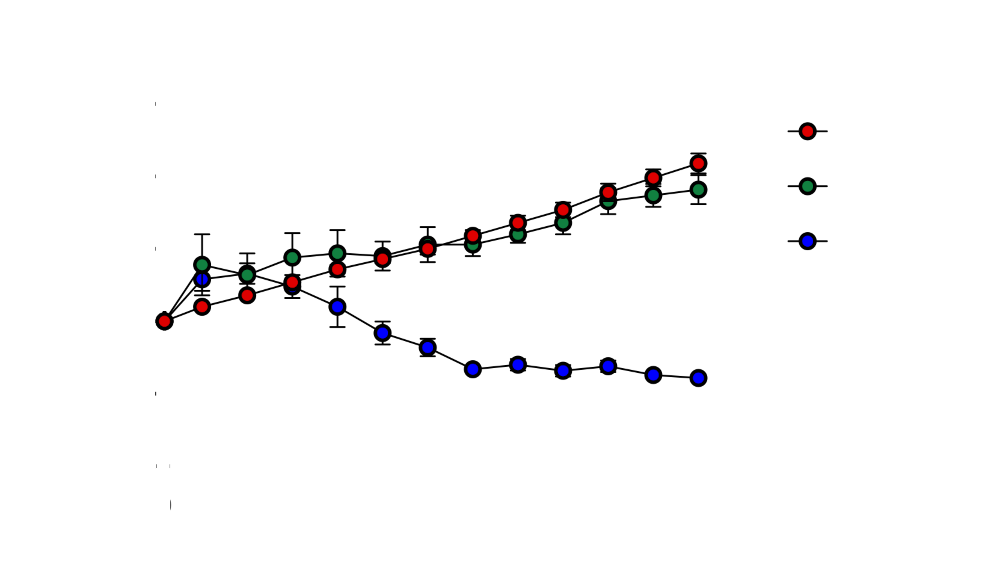

To rigorously evaluate the OFF state, HGI536 was tested in a CRISPR-engineered HepG2 cell line lacking CTNNB1. In these knockout cells, HGI536 showed no detectable cytotoxicity across all tested viral doses, with cell viability indistinguishable from uninfected controls (as shown in Fig.7.). Under the same conditions, wild-type VSV caused rapid and dose-dependent cell death.

We are convinced that our data demonstrates that the aptazyme functions as a stringent replication gate: it effectively abolishes viral replication and cytotoxicity in the absence of the target biomarker, while fully preserving the intrinsic killing power of VSV in cancer cells that express it.

Leave a Reply